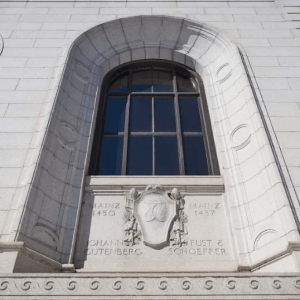

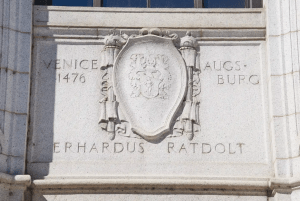

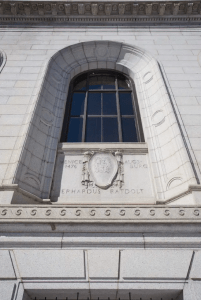

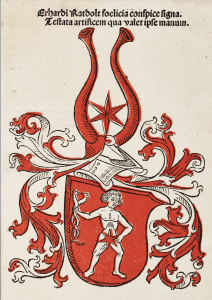

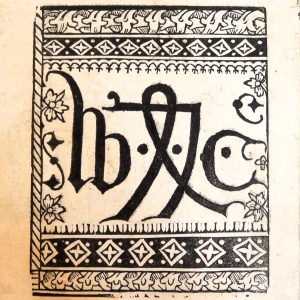

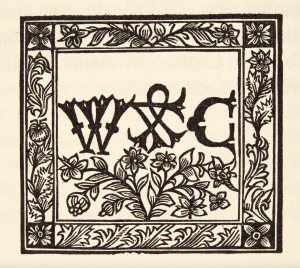

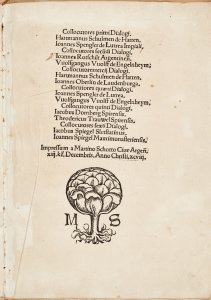

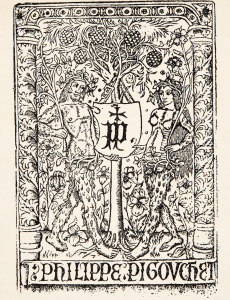

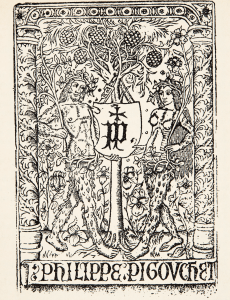

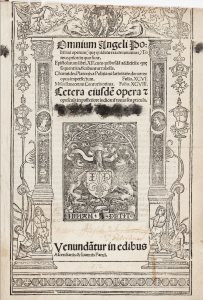

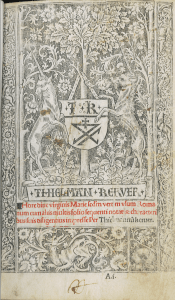

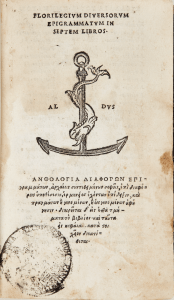

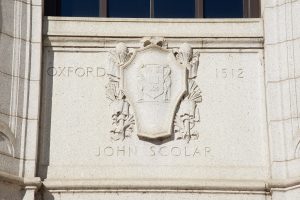

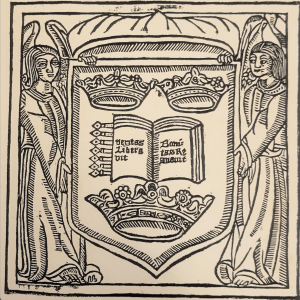

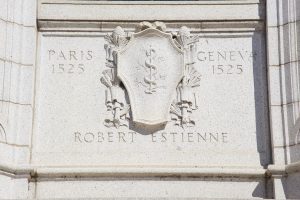

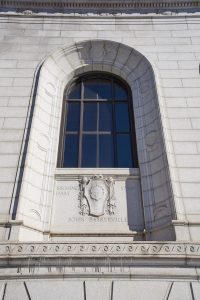

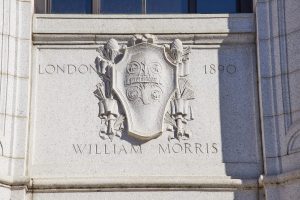

Thirty decorative shields bearing the “Printers’ Devices” or marks of some of history’s most famous printers are carved in high relief on the stone exterior of Central Library just below the arched second floor windows.

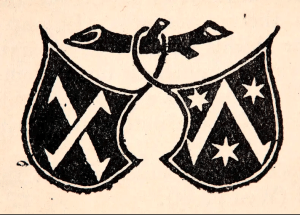

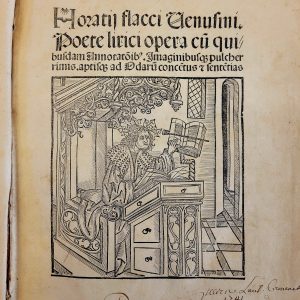

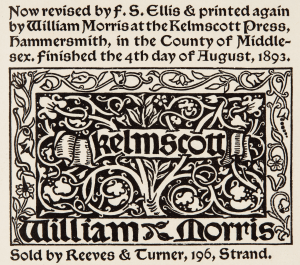

These ornamental emblems, which were typically printed on the title page of a text or the very last page, were devised as a sign of authentication, much like a merchant’s mark or a nobleman’s coat of arms. Similarly, and long before the advent of the printing press, Mesopotamian cylinder seals and Egyptian scarabs were carved to leave unique stamped impressions that could prove ownership or identity.

Although these devices boast masterful woodcut illustrations, for the most part, they were created by unidentified artists. Many early printers had been scribes, calligraphers, and illuminators before printing technology transitioned to the printing press. The fearsome beasts and ornate borders seen in illuminated manuscripts are frequently found in a printer’s mark, along with a monogram and sometimes a motto. The use of the devices peaked in the 15th and 16th centuries.