When you conjure images of people from the late Victorian and Edwardian eras, you might picture grim expressions, stiff clothing, and only the most demure of smiles. There are a few reasons that smiles seem rare in early photography, for example, old cameras required longer exposure times and therefore an almost supernatural ability to stay perfectly still, or perhaps these somber expressions were a carryover from the days of painted portraiture. But there is ample evidence that the photographers and subjects of early photography were having fun behind the scenes, even when their faces didn’t show it, and the Edmund Philibert Photo Collection of glass plate negatives is one example.

When you conjure images of people from the late Victorian and Edwardian eras, you might picture grim expressions, stiff clothing, and only the most demure of smiles. There are a few reasons that smiles seem rare in early photography, for example, old cameras required longer exposure times and therefore an almost supernatural ability to stay perfectly still, or perhaps these somber expressions were a carryover from the days of painted portraiture. But there is ample evidence that the photographers and subjects of early photography were having fun behind the scenes, even when their faces didn’t show it, and the Edmund Philibert Photo Collection of glass plate negatives is one example.

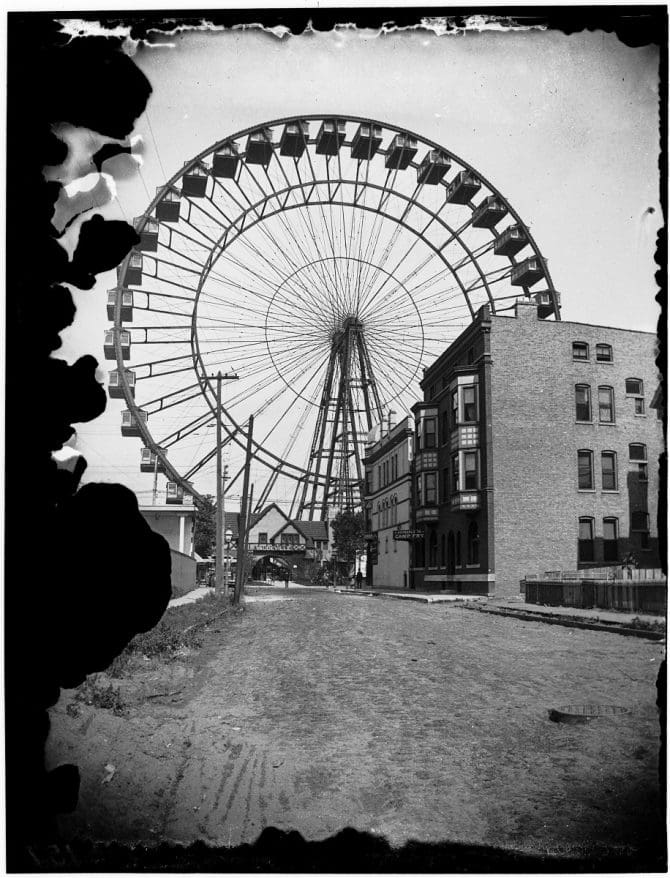

Edmund Philibert was a carpenter who grew up in St. Louis, never married, and relocated later in life to New Mexico with his sister Florence. Much of what we know of his life comes from the detailed diary he kept from his twenty-eight visits to the World’s Fair in St. Louis (published here), and a handful of the photographs in this collection document those visits.

The collection also includes photographs he took in the aftermath of a 1900 fire that destroyed the Penny & Gentles department store in downtown St. Louis.

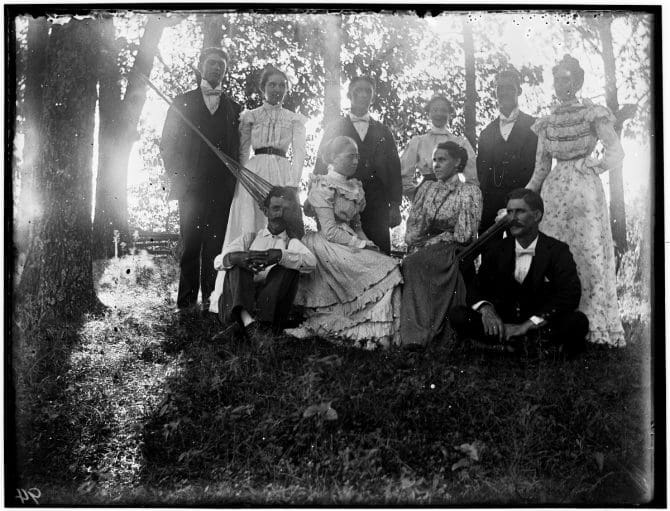

But equally captivating are the photographs Edmund took of his family, including his sisters, nieces, and nephews, both at the family home in north St. Louis and his sister’s farm in Cadet, Missouri. Many are candid photographs of the family tending to a garden, fixing each other’s hair, playing cards together, and just generally enjoying each other’s company.

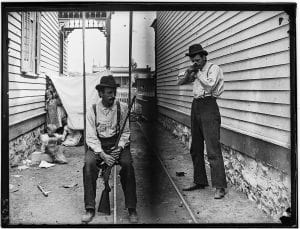

There are a few puzzling photographs in this collection as well. Doppelgangers sit across the table from one another and playfully point shotguns at the camera. Was this a family full of twins or could there be another explanation?

Adobe didn’t release its now ubiquitous photo-editing software Photoshop until 1988, but photographers have been manipulating our perception of reality since at least the late 1800s, when glass plate negatives came into wide usage. Glass plate negatives are made by coating glass with a light-sensitive emulsion, and their large size makes them relatively easy to manipulate. Victorian photographers crafted special lenses, experimented with exposure times, and used collage techniques to create playful photographs of beheaded subjects, spirits, and people interacting with their own doppelgangers. The latter seemed to have been a source of inspiration for Edmund Philibert.

In one of Edmund’s photographs, two men pose with shotguns, one pointing his straight at the camera, in the gangway between two houses. A group of children, who seem to be in on the joke, peer out from behind a sheet that has been hung from the porch. It’s the curious dark line down the center of the photograph, combined with the fact that the two men look suspiciously alike, that tips off the viewer that this photograph might not be as it seems. In another photograph, Edmund’s young niece Jane shares a plate with her doppelganger on the other side of a table. Edmund may have used a device called a duplicator, which covers one half of the lens at a time, to create his double exposure. These photographs may not be the most convincing examples of trick photography, but that’s part of the charm. Edmund wasn’t a professional; he was an everyday person experimenting with a new medium.

In other unaltered photographs, Edmund’s sister Angie shares a smile with a friend while a horse passing in the background turns to look directly into the camera. A boy poses on his bike. The photographer’s mother plays a solitary game of cards. This collection of glass plate negatives give us a rare glimpse into the life of a family that clearly enjoyed each other's company, and they reveal a photographer with a clever sense of humor. Though as far as we know, Edmund never married and never had children, he still left his mark on the world.

All 108 images are now available online in high resolution on our Digital Collections site in the Edmund Philibert Photo Collection.

~ by Rebecca Brown-Gregory

Add a comment to: Pranks and Illusions in the Philibert Photo Collection